Endometriosis is a very common condition, affecting about 7% of reproductive-aged women -approximately 5 million Americans. Although they may suffer symptoms ranging from pelvic pain to infertility, many women do not know that they have endometriosis. Fortunately, our understanding of (1) the clinical presentation of endometriosis, (2) its proper diagnosis and staging, and (3) the management of its sequela have improved dramatically over the past decade. The result has been improved diagnostic and therapeutic options and better, more comprehensive patient care.

Definition

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue (normally found only on the inside of the uterus) in locations outside the uterus. Endometriosis is most often found in the pelvis (on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, or bladder), but it has also been found in sites outside the pelvis (including omentum, small intestine, appendix, anterior abdominal wall, surgical scars, diaphragm, lung, urinary tract, and musculoskeletal and neural systems). This endometrial tissue reacts to hormonal changes (estrogen and progesterone) during the menstrual cycle, just as endometrial tissue lining the inside of the uterus reacts during the normal ovulatory cycle.

Prevalence and Incidence

The prevalence and incidence of endometriosis depends on the population of women being studied. It has been reported to occur in 10 – 15% of women undergoing diagnostic laparoscopy, 2 – 5% of women undergoing tubal sterilization, 30 -40% of infertile women having laparoscopy, and 14 – 53% of women with pelvic pain. It is a very common condition.

Pathophysiology

There are several theories that attempt to explain how endometriosis develops. One popular theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes, with subsequent implantation and growth of endometrial cells contained in the menstrual blood. Other theories involve metaplasia (normal tissue in the abdominal cavity spontaneously changing to endometriosis), direct implantation of endometrial cells into the abdomen during surgery, and spread of endometrial cells from the inside of the uterus to other locations via blood vessels or lymphatics. Each of these may contribute to endometriosis in different patients. Immunologic problems most assuredly play a role in the development of endometriosis.

Numerous factors influence a woman’s risk of developing endometriosis. These include:

- genetics (an affected sister or mother doubles the risk)

- hormonal status (higher estrogen levels and prolonged heavy menses increases risk)

- lifestyle (low body weight and cigarette smoking reduce risk by decreasing estrogen levels)

- contraceptive use (oral contraceptives possibly reduces progression of disease)

- obstetric history (pregnancy and lactation reduce risk)

- anatomic factors (cervical stenosis increases risk)

- treatment history (prior medical or surgical treatment reduces risk)

- race (Caucasians are at higher risk than African Americans)

Endometriosis is thought to cause infertility by distorting anatomy, creating hormonal abnormalities, altering the pelvic biochemical environment, influencing the immune system, interfering with sperm function, and (possibly) altering the process of embryo implantation.

Endometriosis causes pelvic pain primarily by an intense inflammatory response around the implants. This is particularly severe during menses, since the implants may also bleed now. This inflammation often results in pelvic adhesions, which can also cause pain. The location, size, and depth of penetration of the endometrial implants strongly influences the type, intensity, location, and duration of pelvic and abdominal pain.

Clinical Presentation

Approximately 80% of patients with endometriosis present with pain. About 20% of those patients are also infertile. 5% present with a “tumor” of endometriosis in one or both ovaries (these are called endometriomas). Anywhere from 5 to 40% of patients with endometriosis will have no symptoms at all.

The intensity of a patient’s pain may not correlate with severity of her endometriosis. Minimal disease may produce the worst pain. Pelvic pain from endometriosis may be the result of:

- endometrial implants secreting irritating factors (e.g., histamine)

- scar tissue (adhesions)

- leaking endometriomas (tumors of endometriosis in the ovaries)

- compression of other abdominal structures (e.g., bowel, ureter)

- compression of endometriotic nodules deep in the pelvis

- invasion of the urinary tract (bladder or ureters)

- invasion of the gastrointestinal tract (small bowel or colon)

Even in patients with minimal and mild disease (AFS stage I or II), endometriosis is likely associated with infertility, although it may not be the primary factor. A cause-effect relationship most certainly exists for moderate and severe disease (AFS stage III or IV). These patients usually have adhesions, deep invasive lesions, and endometriomas. Endometriosis may also be associated with structural abnormalities and damage to the fallopian tubes. Studies do not, however, support an association between endometriosis and increased spontaneous miscarriage rates.

Endometriosis lesions occur throughout the pelvis. They are most commonly found in the posterior cul-de-sac (between the back of the cervix and the rectum) and the ovary, and less frequently on the fallopian tubes. Lesions on the surface of the bladder are also common. Endometriosis is almost certainly a progressive disease, but the rate of progression and nature of lesions varies enormously from patient to patient.

Adhesions develop around endometrial implants because of the inflammatory process surrounding the disease, with more extensive and dense adhesions developing over time. The worst adhesions in the most advanced cases often involve the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and lower colon (near the rectum). Laparoscopic surgical treatment of these cases is always preferable, but demands skill, extensive experience, and patience on the part of the operating surgeon.

Although endometriosis can be “suspected” by taking a comprehensive history and performing a pelvic examination, it can only be diagnosed by surgically inspecting the pelvis. This is almost always done by laparoscopy (belly-button surgery).

When a woman undergoes laparoscopy to diagnose and treat endometriosis (and it should almost always be treated at the time it is diagnosed), 2 steps are critical: 1. The surgeon should biopsy several areas of the pelvis suspected of being endometriosis to confirm the diagnosis, and 2. The surgeon should take numerous photographs of the pelvis, uterus, ovaries, bladder, and fallopian tubes. These photos should be taken before and after treatment to document the procedure. All areas of endometriosis should be photographed.

In addition, the patient should be supplied with copies of these photos along with the operative report of the procedure along with the pathology report.

The diagnosis of endometriosis may require a long-term management plan spanning years or even decades. Comprehensive, detailed photographic documentation of the surgical findings when 1) endometriosis is first diagnosed, and 2) Treated during subsequent surgeries is invaluable in making treatment recommendations years later.

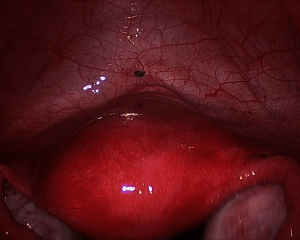

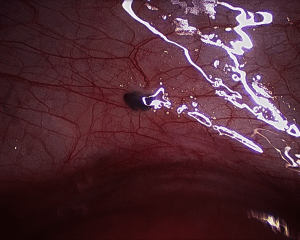

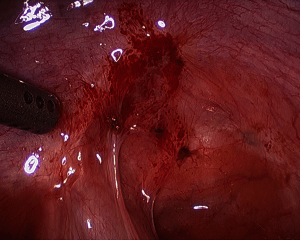

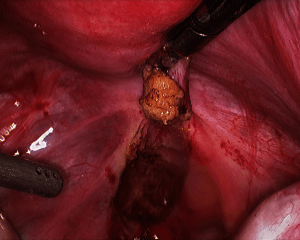

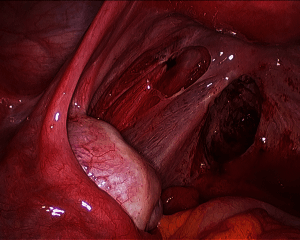

The photographs below demonstrate the varied appearances of endometriosis in the female pelvis.

The black lesion is endometriosis overlying the bladder, just above the uterus

The reddened area behind the uterus is a large nodule of endometriosis. On the right, the nodule is about to be removed. It is about ½ inch in diameter and ½ inch deep.

Endometriosis above and below the uterus has been removed.

Endometriosis beneath the right ovary